At the Century Villages of Cabrillo, where she volunteers at CityHeART, Melissa Degnan sits near a mural honoring veterans.

RACHEL LIVINAL / NEXTGENRADIO

home?

Rachel Livinal speaks with Melissa Degnan, a U.S. Army veteran and volunteer at City HeART, a non-profit organization in Long Beach. Degnan experienced PTSD and home insecurity after her military service before she finally found home and friends in Long Beach. Her past motivates her to help other veterans and people in Long Beach who experience homelessness.

From skinny trees to social hours: An Army vet’s journey home

Listen to the audio story.

Click here for audio transcript

I’m Rachel Livinal with NPR’s Next Gen Radio In Los Angeles.

For some U-S Veterans, returning home may not be what they imagined.

Veteran Melissa Degnan spent years in dangerous living situations, and her meaning of home was hard to define.

After finding a community of people like herself, she found home is giving back.

—

My apartment is my home. And then this is my place to come. This being City Heart is my place to interact with people. In a situation where I’m helping them instead of being helped myself. Because by me helping them I am helping myself.

My name is Melissa Degnan.

I’m 67 years old.

I volunteer at City Heart.

City Heart is a not-for-profit organization that helps people in the community.

I was in active duty for quite a while, both five and a half years enlisted, nine and a half years as an officer and I was stationed in different places in the world.

My favorite job when I was enlisted was, um, being attached to the 18th EOD Explosive Ordinance Disposal detachment, which was the military equivalent of the bomb squad.

Being in the military, as long as I did it, being in the military community felt like home to me.

I guess it took me so long to adjust. Because I moved around as a kid a lot. And then I moved around in the military a lot. And I wasn’t even used to being in one place for such a long time.

I spent about five and a half years on the streets. I was very mentally ill and didn’t know that I was mentally ill. So I used my military skills to keep myself hidden from people. And there were some people that knew of me, and they were trying to get me to come in.

But that just made me even more paranoid. And I ended up staying in women’s advanced for two and a half years until it was my time to transition into more permanent housing.

And I got beat up twice in less than a year. I mean literally black and blue kind of beat up. Oh, and I also had a kitten and somebody poisoned it and killed it and so with them not responding well to my getting attacked and the death of my kitten and I made a decision to move and that’s when Reggie helped me out.

Reggie is one of my best friends. And he’s also a volunteer.

And as you can see, we’ve got a lot of donations. And so they’re in bags. And we don’t have them separated yet. That’s something that Reggie and I do.

And as the joke we have we have wedding dresses in the closet, and the bathroom actually hanging off of the of the shower or bathroom stall, as you can see, and one of these is my size. So the joke was, we go to the toy section, get a plastic gun, me put the dress on. And then we have a shotgun wedding with Reggie.

I have no family so…. Home is wherever I am. And whatever friends that I make.

Over a 24-hour period in October 1989, Melissa Degnan boarded a military helicopter and survived an emergency landing, hid behind what she remembered as the “world’s skinniest tree,” and buried the uniform she was wearing.

She was in Honduras serving in the U.S. Army when the helicopter she was in experienced a hard, not-quite-crash landing. As she and the other passengers got out, people on the ground pointed weapons at the crew and demanded they hand over Degnan’s general. Degnan and the crew ran.

After racing through a wooded area, Degnan came upon what looked like a populated area. From a nearby clothesline she grabbed a pair of pants and a brown shirt. Leaving some local currency for whomever’s clothes she took, Degnan then walked into a nearby store and bought a straw hat and a flowery white blouse to try to disguise herself as a local.

Degnan accepts a certificate for service, which she received about 35 years ago while stationed at Redstone Arsenal in Alabama.

PHOTO COURTESY OF MELISSA DEGNAN

Degnan, 67, served in the U.S. Army for 15 years, much of it working in an Explosive Ordinance Disposal (EOD) detachment, the military equivalent of a bomb squad.

“It was a lot of fun,” Degnan said. “We went into impact areas or somebody would find a round somewhere, and they’d bring it home, not realizing how dangerous it was. And then we (would) take it and destroy it.”

About a decade after leaving the military, Degnan’s mother died and she found herself taking care of her aging father. Some years later she felt something was “wrong” and couldn’t hold down a job. She ended up living on the streets of Southern California for five and a half years.

Several years ago Degnan connected with CityHeART, a nonprofit organization that serves the houseless, formerly houseless and veterans. Since then she’s become one of its most prominent volunteers.

One afternoon this March, Degnan showed a reporter around the office, pointing out the supply rooms and computer lab. She stopped in a small living room with a filled bookcase, a TV, a piano and a couple of couches.

“This is our social (lounge),” Degnan said. “Our people get here and we just chit-chat.”

In what she calls the social hour, Degnan hangs out with friends she’s made through volunteering and tells “war stories.” Her story about the attempted coup in Panama is a long one, and she has several other funny ones. One story Degnan tells often is about a rattlesnake biting her boot at Fort Irwin in San Bernardino County.

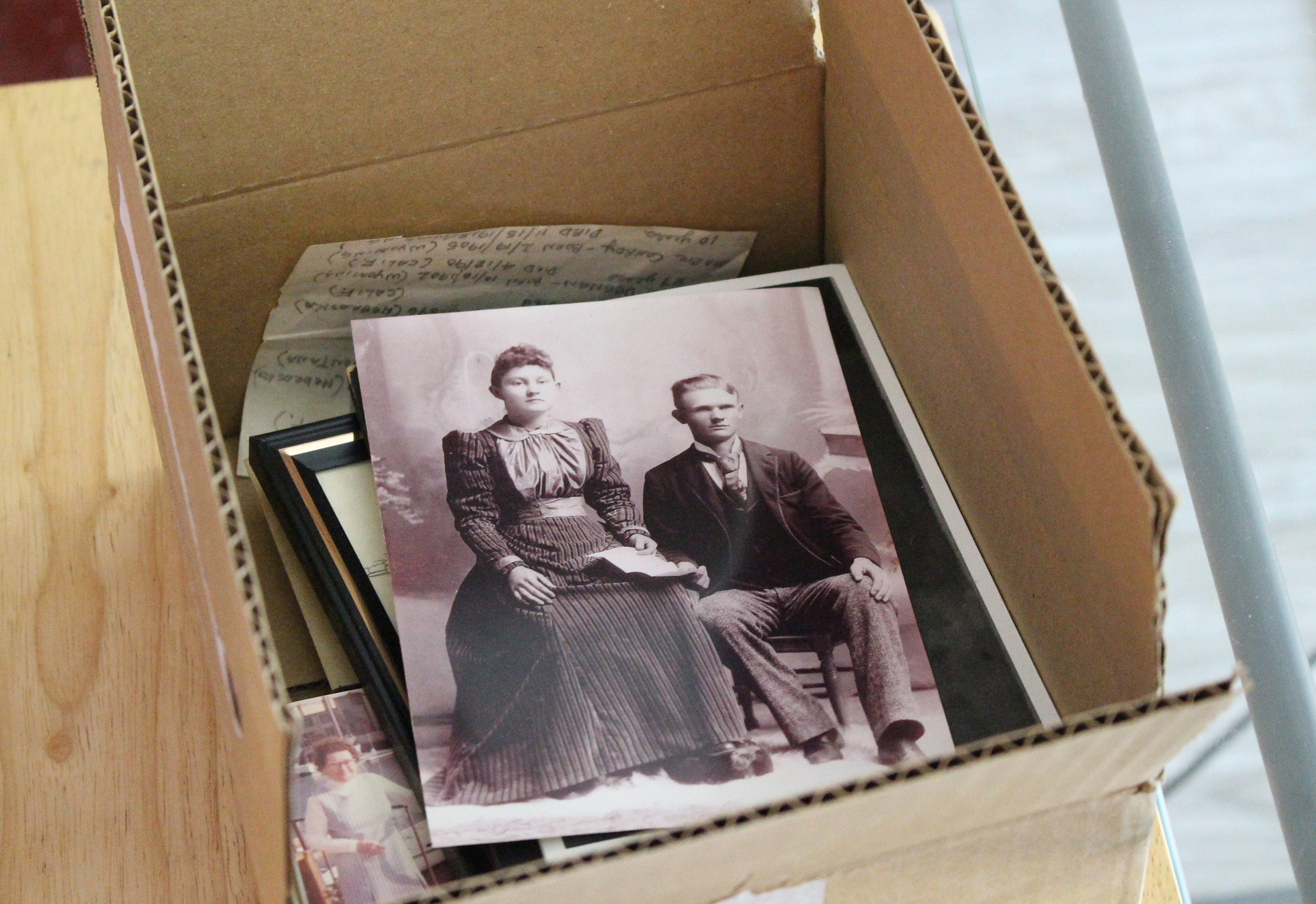

After years of moving around, Degnan only has one small box of family photos and memorabilia remaining. She said the top photo is one of her grandparents.

RACHEL LIVINAL / NEXTGENRADIO

Degnan volunteers at CityHeART three times a week. On Mondays she goes through two small, stuffy rooms full of baby onesies, shirts and shoes, a tiny enclosed space filled with boxes of diapers, toothpaste and other necessities, and a kitchen with a tower of boxes of canned food. She pulls together items from each of these areas and assembles bags to distribute to CityHeART families.

Among the items for donation are about a half-dozen wedding dresses. Degnan felt they were too special to store alongside pantry goods, personal-care products and children’s clothes, so she decided to set them aside in the bathroom.

“If I put them in the normal clothing room, the gowns wouldn’t be shown off to their finest,” she said. “And those are beautiful gowns.”

Degnan volunteers at CityHeART in Long Beach, which provides resources to the community and receives donations for various types of food and clothing, including wedding dresses. The center has limited space for all of the donations, so Degnan put the dresses in the bathroom and hung them from the shower curtain rod.

RACHEL LIVINAL / NEXTGENRADIO

There was a time when Degnan fit the mold of the people she helps. She was houseless and living with “mental illness,” and she would’ve spent more years on the streets if she didn’t stumble into the help she needed.

She was misdiagnosed, then diagnosed again, with PTSD, prescribed different medications, and finally put onto a list for permanent housing. After years without a place to live, she eventually transitioned into housing with the U.S. Vets Advance Women’s Program for Transitional Housing.

More than two years later, Degnan got an apartment at the Central Villages in Cabrillo, a special housing unit for those transitioning out of homelessness and what Degnan describes as the “internal community” of CityHeART. The organization is located within the complex.

Degnan and Reginald “Reggie” McClain sit together on a bench outside CityHeART in Long Beach, where they both volunteer their time. The two are veterans and best friends, live in the same housing complex and go grocery shopping together frequently.

RACHEL LIVINAL / NEXTGENRADIO

In 2019, Degnan moved in, but three years later, she moved out. Twice she experienced harassment by people on bicycles, and on one occasion her assailant threw her to the ground and kicked her repeatedly. She filed a police report against both men, but the first person was never found, and the second was never charged.

After that, her kitten was poisoned and died, so by 2022 she decided to move. Her best friend Reginald “Reggie” McClain helped her transition to her current home: Gold Star Manor. According to the complex’s website, the site “provides independent living” for veterans and seniors.

McClain provides Degnan a sense of family, and they both hang out frequently.

“Right now, we’re putting up (shelving) for each other,” Degnan said.

Degnan feels safe in her new home, in a way she hasn’t felt for years. She is still settling in but is grateful for everything she owns — almost all donations, much like the donations she gives to those who visit CityHeART.