Ryan Wimsatt lives with his family in Windsor Hills, Los Angeles. After returning home from college, Wimsatt decided to come out to his family.

PALOMA MORENO JIMÉNEZ / NEXTGENRADIO

home?

Paloma Moreno Jiménez speaks with Ryan Wimsatt, a young queer photographer who grew up in the Windsor Hills neighborhood of Los Angeles — also known as the Black Beverly Hills. At home, his parents celebrated his Black identity and encouraged him to be anything he wanted to be. But his queer identity didn’t fit within the dreams they initially had for him. For Wimsatt, home is a place where he can grow — and where the people he loves can grow, too.

Coming out and coming home

Listen to the audio story

Click here for audio transcript

Hi! I’m Paloma Moreno Jimenez with NPR’s Next Gen Radio in Los Angeles.

Ryan Wimsatt has two homes.

One with his loving family, and the other with a group of college friends who nurtured his queer identity.

Wimsatt is trying to create a new definition of home that reconciles the two.

[Sound of creaking steps/birds]

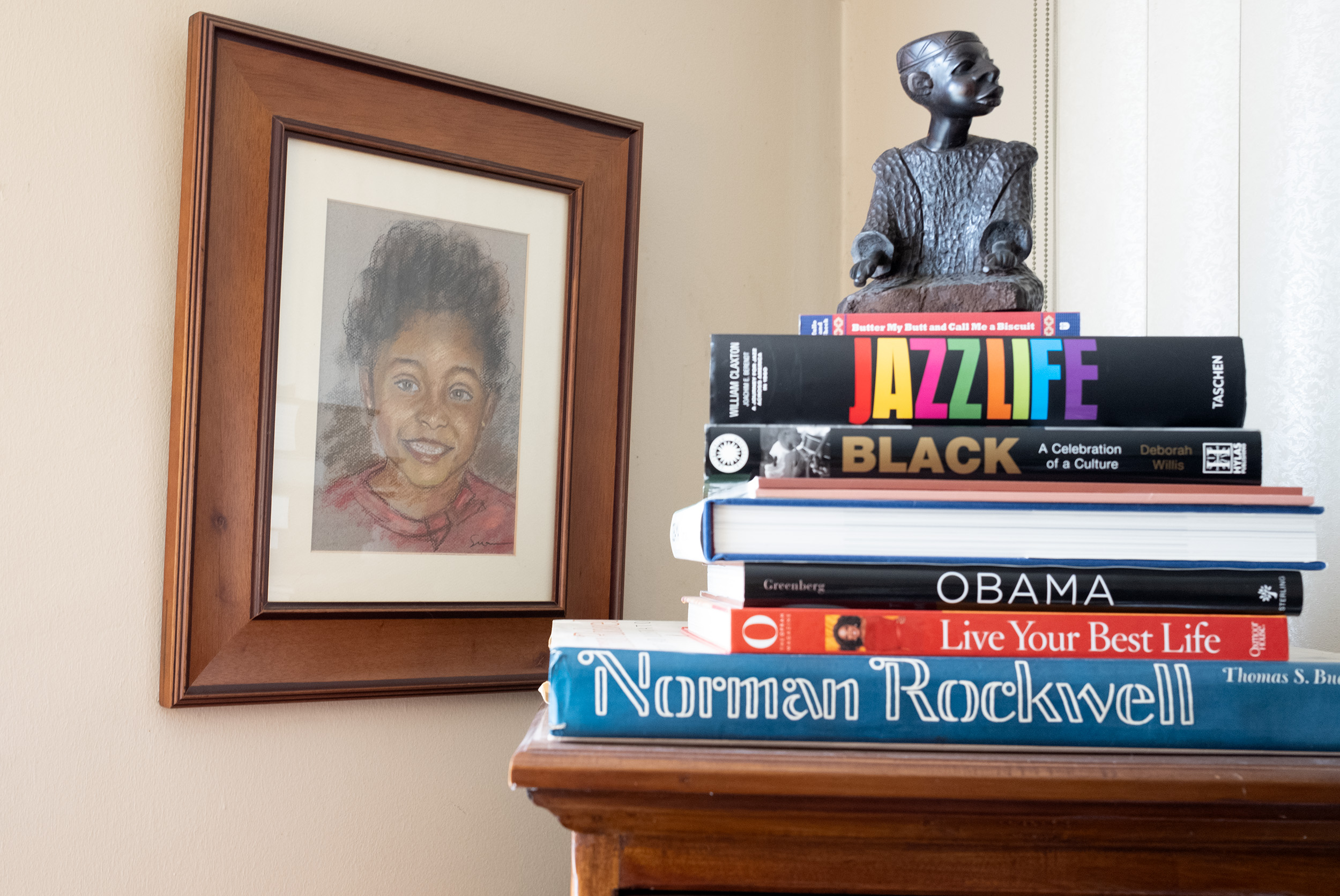

So this wall we’re looking at is, um, kind of a collage of older paintings kind of art, black art. So we have a couple drawings of little black children.

When I come to this space, it reminds me of how my parents have been very intentional in making the home a place to kind of see yourself and know that, oh, I, I am, I’m worth painting and drawing and being created into art.

[Sound of door unlocking]

Hi, um, my name is Ryan Wimsatt. I am 23 years old, and I am currently living in Windsor Hills, California, Los Angeles, my hometown.

My parents came to this neighborhood looking for a home. It was called Black Beverly Hills, and my dad and my mom really wanted to live in a black neighborhood that was nurturing, kind of akin to the art within the home.

Growing up in a black neighborhood definitely impacted my, my view of myself.

I was given an opportunity to, to think for my own opinions, have my own dreams…and grow.

When I realized, oh, I actually might be queer and…not feeling like that reality of mine was best serving my parents.

Especially going to college and realizing that this is who I am and I need to be honest to myself and I owe that to myself as well…

Being in the home felt like I had was regressing. And It had come to a tipping point and I remember telling my mother…and then coming to a place of tension in who I am.

She said, you have these expectations for your children. There is a mourning that comes in understanding that your chi, that your child isn’t going to meet or do the things that you always dreamed for them.

I think that is where a lot of the disappointment or upset kind of came from because I would say, oh my gosh, my mother, she’s a psychology sociology professor. She’s, it’s all about elevating the black experience. How could she be so blind to this in me? , and I say…this often and I at least my friends know when I say it to my friends, I say, you know, being, being pro-black or being a person of color and wanting the best for your, your race or ethnicity is not the same as being pro the human experience for everyone.

You know you know things until someone else of that experience kind of teaches you it. And that’s kind of where she is. She’s really understanding and learning as well, and she’s becoming a partner in this.

Before it felt like when I go to college and I’m hanging out with my friends, there is where I exist in a home. That’s where I can be myself and my queerness. And my physical home is where I can exist with my family, but now I feel like they’re coming together really beautifully with time.

And maybe it’s as simple as that. Maybe home is just a safe place where I can grow.

Ryan Wimsatt has two homes — one with the loving family that raised him and another with the friends who supported him as he came to terms with his queer identity.

“Home to me is a place or people where you feel safe and you have room to grow,” the 23-year-old man said. “It’s a group of people who nurture you and make you feel seen and heard, but push you to do the best that you can.”

Wimsatt’s understanding of home began with his family in Windsor Hills, California, one of several neighborhoods known as the “Black Beverly Hills.”

Wimsatt said this choice of neighborhood was deliberate.

“My dad and my mom really wanted to live in a Black neighborhood that was nurturing,” he said. “Just letting a family kind of see themselves being successful, see themselves as valuable.”

ILLUSTRATION BY EEJOON CHOI / NEXTGENRADIO

This collection of art was passed down to Ryan’s father from his aunt. It is an example of how Ryan’s parents surrounded him with pieces that he could see himself in. His parents were very intentional about making a home that celebrated him as a young Black man.

PALOMA MORENO JIMÉNEZ / NEXTGENRADIO

This sentiment is also reflected inside the family’s one-story stucco home. Wimsatt’s mother, Carman, decorated their living room with Black art — including a collage of paintings and drawings of Black mothers and children, and a glass case that displays ceramics of Black figurines.

“My mother was raised in her grandmother’s house and she says she didn’t have a lot of Black art in her home,” Wimsatt said. “It reminds me of how my parents have been very intentional in making the home a place to kind of see yourself … and know that, oh, I’m worth painting and drawing and being created into art.”

Wimsatt’s parents encouraged him to explore his interests. His mother took him on road trips where Wimsatt could practice his photography. They wanted him to pursue his creative passions even if they weren’t his full-time career.

But for Wimsatt there was one aspect of his life that he didn’t feel comfortable sharing within his home — his sexuality. Wimsatt said his parents were never openly homophobic, but they were uncomfortable with queerness.

“I call it ‘northern homophobia’ and that there’s a little bit of fear there, but it’s not overt,” he said. “The conversations then were just more behind closed doors, not really discussed.”

It wasn’t until Wimsatt went to Stanford University that he began to explore his queer identity.

“When I went to college, I met my friends and they were all queer,” he said. “I always say, ‘God subconsciously gave [me] a group of people that were going to receive me when I was ready,’ and that definitely happened.”

Ryan described his mother, Carman Wimsatt, as the heart of the home. Their relationship is very close – they go on roadtrips together where Ryan can practice his photography.

COURTESY RYAN WIMSATT / NEXTGENRADIO

While Wimsatt felt at home with his friends at Stanford, it took him time to feel ready to come out to his family. Part of his hesitation stemmed from his parents’ discomfort with queerness. But he also wasn’t ready to relinquish a role he had taken on after the death of his younger sister Jenna, who died when she was 6. Wimsatt was only 9 years old at the time.

“When my sister passed away, when I was younger, my parents didn’t stay as just parents. To me, they had transformed into grieving parents,” he said. “So if they’re unhappy, it might be because of me, because the hyper fixation on me is a product of the absence of another child to focus on. And that’s where my child’s brain kind of landed.”

Ryan is pictured here with his group of friends at Stanford University. He describes them as his non-physical home and the people he first came out to.

COURTESY RYAN WIMSATT / NEXTGENRADIO

A drawing of Ryan’s younger sister, Jenna, was gifted to his parents after her passing. It is one of the many images of her around the house.

COURTESY RYAN WIMSATT / NEXTGENRADIO

ILLUSTRATION BY EEJOON CHOI / NEXTGENRADIO

But his college friends encouraged him to be honest with himself.

“I had to relinquish the protector role back to my parents and let them nurture me and let them show me that they loved me, including my queerness,” he said.

Wimsatt came out to his mother at home during his senior year of college.

“There was some silence that entered the room,” he said. “We kind of looked at each other a couple times, then looked at the floor and … ultimately, we both ended up crying silent tears. Like the tears you have when you know you’ve caused someone some sort of pain that was unintentional.”

But Wimsatt and his family have made a lot of progress in the two years since that moment. Over breakfast, his mother told him that she wanted to be given a chance.

“Ryan, I’m not perfect, and in no way would I hope that you looked at a couple moments of me and think that that meant everything about you. I hope that in no way has a reaction of mine made you feel like you were living in conditional love,” Wimsatt recalls his mother saying.

Wimsatt sees home as a place to grow — and he wants to give his family the same opportunity.

“My mom needed to definitely feel that she could grow in the house as well,” he said. “It’s her home and this is her family, and I’m her son.”

Ryan and his mother set up two chairs right outside their home’s entryway, where they like to enjoy their coffee and chat while overlooking their street.

PALOMA MORENO JIMÉNEZ / NEXTGENRADIO