Philip Thang stands outside the Project Rebound office at California State University, Los Angeles, where he helps formerly incarcerated individuals transition into the California State University system.

ZAYNAH WASEEM / NEXTGENRADIO

home?

Zaynah Waseem speaks with Philip Thang, a sociology student at Cal State LA. Thang was incarcerated at the age of seventeen for shooting at a rival gang member from a moving vehicle. He was sentenced to 70 years to life in prison. While in prison, Thang dedicated himself to pursuing education and was released in 2020 after serving 20 years. Now, he works at Project Rebound at Cal State LA, where he supports formerly incarcerated individuals pursuing higher education. Thang considers his faith to be an integral part of his life, through which he has found a sense of purpose and an understanding of home.

Formerly incarcerated student finds home in his faith

Listen to the audio story

Click here for audio transcript

Hi, I’m Zaynah Waseem with NPR’s Next Gen Radio in Los Angeles.

Philip Thang spent 20 years in prison.

He never thought he’d go home.

But he did and discovered home was more than just a place… It was spiritual.

I was tired of being tired. I wanted to make my family proud. So what I did is, you know, I got my G.E.D in prison. I was able to apply for college, community college.

My name is Philip Thang. I’m a student here at Cal State LA, my major is sociology.

I’m a refugee baby, so born in the Philippines. But I’m Cambodian.We moved to Pomona Valley, and that’s where I got involved in gangs, because that’s all I knew, that’s all I saw growing up. You know, we had nothing so these guys have nice cars. They have nice clothes. You know, I’d have the pretty girls and I wanted to be that.

But it was cut short at the age of 17 when I committed a crime, at a rival gang member, I shot at them from a moving vehicle. Thank God nobody got hurt. But. However, they made a example out of me. And at the age of 17, the judge said, ‘well you act as an adult so I’m going to send you to prison like an adult.’ I’m going to give you 70 years to life. And from there, my life, you know, just ended was at I well not ended, but it paused.

But when I finally came to that aha moment where I, you know, like, what’s the purpose of living, right? Well, why my life when I asked myself that question that I found purpose. Right. And I started to dive deeper and go to church, and I’ll get deeper with my faith. And that’s when I truly changed when I realized, you know what. Even if I die in prison, at least I’m going to die doing good, in prison. Cause I didn’t know when I was going to home, but I’ll make my family proud.I’ll make myself proud.

So in 2015, they finally told me, you know, you know you have a chance to go home. They’re like, you know what we’ve seen that you’re doing good. What is it? What happened? What what clicked in your in that time frame? I tell them, we’ll at the age of 24 or 25, I just my brain just started thinking different.

I got out during the pandemic.It was my silver lining. I needed to transition to society slowly.For example, I went to a store with my dad and he said, Yeah, buy whatever you want son whatever you need for the house.I just stood there. I didn’t know what to do with so many options. It was just too much for me to take in so I told dad you need to shop cause I can’t do it.

It’s traumatizing being in there. And, you know, for example, just hearing an alarm, I feel like just laying like sitting down because that’s what we were trained to do for 20 years. And funny thing is, I have keys and I like wearing my keys. I hear the key ring. Some are like just jiggle because I was so comforted by the keys at nighttime, when the correction officer does count, it comfort me for some reason. I know what. It’s count time everybody’s locked up in their cells? Nobody’s gonna hurt me. So the key is, as a representative of me being safe.

I actually surprised my parents when I got out. After 20 years I told my brother, hey look, I’m getting out, but don’t tell Mom and Dad because my dream was. My ultimate dream. I dreamt it so many time was to surprise my mom so I walk I walk out of the car with flowers and then she didn’t think of me, she thought that I was like that was like so pale at that time. It’s like who’s this white guy with flowers at that moment. Right. And then she started crying and we hugged and she, she was just so in shock she’s like, the first thing she said as a parent. Of course, Son, why didn’t you tell me you were getting out, I could have made something for you to eat.

I go to church every Sunday. You know, my faith is what sustains me the most. And that’s what I want to kind of emphasize on that as home is my faith. It’s what helped me to have purpose you know and see it in another light.

I realized home, it’s not here on earth.

ILLUSTRATION BY SHIDEH GHANDEHARIZADEH

Philip Thang now relishes the ordinary and mundane.

“Just going to the supermarket, taking my mom to the supermarket and watching her shop was a dream come true for me. I dreamt that moment. Just take my mom to the store, you know, just help my dad around the house,” he said. “I realized that the joy in life is just the small things, not the big things.”

Thang, a sociology student currently enrolled at California State University, Los Angeles, was sent to prison when he was 17 for shooting at a rival gang member. He was sentenced to 70 years to life in prison, but two decades later, in 2020 during the pandemic, Thang was released after demonstrating self-improvement and a commitment to higher education.

“I did it because I was tired of being tired,” he said. “I wanted to make my family proud.”

Now, along with being a student, Thang is giving back to the community and helping others through his involvement at Project Rebound, a program designed to assist formerly incarcerated students transition into the California State University system.

A struggling childhood

Thang identifies as a “refugee baby.” His parents escaped the killing fields in Cambodia and moved to the United States in pursuit of a better life. They eventually settled in Pomona, California. That’s where he became involved in gangs.

“Growing up in this type of environment, the poor neighborhoods, you aspire to be what you see,” he said. “We had nothing. So I saw in front of us all these guys have nice cars. They have nice clothes. You know, I’d have the pretty girls. And I wanted to be that,” he recalled.

While no one was injured when he shot at a rival gang member from a moving car, he was sentenced as an adult.

“From there, my life, you know, just ended. Well, not ended – but paused,” he recalled.

Finding home in his faith

For the first seven years of being incarcerated, Thang said he was battling with himself.

“I was my worst enemy, trying to prove to people and be somebody,” he said.

But eventually, he said he came to an “aha” moment and began to self-reflect on the purpose of life, allowing him to ultimately get deeper with his faith and started attending church.

“That’s when I truly changed. And I realized, ‘you know what, even if I die in prison, at least I’m going to die doing good in prison,’ because I didn’t know when I was going to go home,” he said. “I realized home is not here on earth, for me it’s now more spiritual. I see walls, but God doesn’t see walls.”

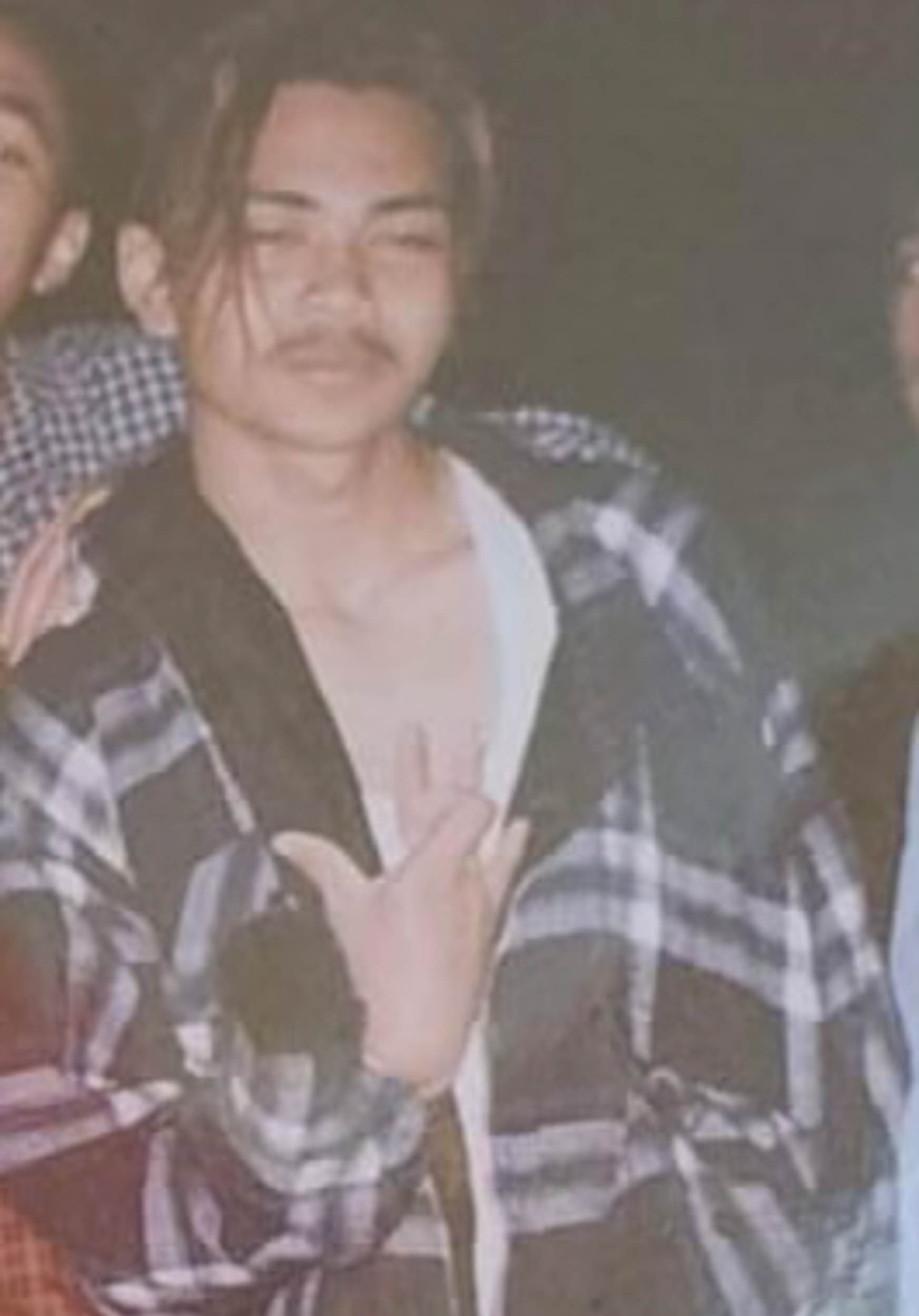

Phillip at 17 holding up a gang sign. He later shot at a rival gang member and was sentenced as an adult.

PHOTO COURTESY: PHILLIP THANG

ILLUSTRATION BY SHIDEH GHANDEHARIZADEH

From pursuing gangs to pursuing an education

With that in mind, Thang was determined to improve his situation and started attending a self-help group. He also realized the importance of education and the power it had to open new doors. While in prison, he got his GED and was able to apply for community college. His efforts in not only improving himself but also pursuing higher education became fruitful when he was told he would have a chance to go home. Thang left prison with not one, but multiple associate degrees.

The transition back into society hasn’t been easy, though he said being released during the pandemic was his “silver lining” because he needed a slower pace to readjust to society. He recalls being in a grocery store with his dad and being overwhelmed by the choices. He said he couldn’t hear an alarm without feeling like sitting down on the floor because that’s what he was trained to do in prison.

And often, he’ll walk with his keys in his pocket just to hear the jingle – a familiar sound that comforts him. When guards walked around at night, the sound of their jingling keys meant everyone was locked in their cells, and he would be safe.

The first thing Thang did when he was released was visit a church.

Faith has played a critical role in his journey. For Thang, helping others has allowed him to make a difference and make his family and himself proud.

“That’s what I strive to be, is to help,” he said. “To help the poor, right? Because I was poor. And Project Rebound is one of the ones that, you know, help the poor, which is formerly incarcerated students.”

Thang believes that if you bless others, a blessing will come right back, and that love is wishing the other person the best.

Now, Thang is working toward graduating and has applied to graduate school for sociology. He said he wants to continue to work with troubled youth.

Philip is pictured here in the middle with his family members at the time of his incarceration.

PHOTO COURTESY: PHILLIP THANG

The day of Philip’s release, the first place he visited was a church where he could sit and pray. His faith continues to play an integral role in his journey.

PHOTO COURTESY: PHILLIP THANG

Philip with his family members at the Pier the day of his release.

PHOTO COURTESY: PHILLIP THANG